ZeroDP: Just-In-Time Weight Offloading over NVLink for Data Parallelism

Maximizing LLM Throughput with ZeroDP

High-throughput inference for Large Language Models (LLMs) is a constant battle against GPU memory constraints. While compute capacity often dominates the conversation in training, production inference is frequently bottlenecked by memory capacity—specifically, the space available for the Key-Value (KV) Cache.

In a typical Data Parallel (DP) setup, we shard our traffic across multiple copies of a model. However, DP comes with a heavy tax: redundancy. Every instance holds an identical, full copy of the model weights. If you are running Qwen-30B on two H100s, you are storing two identical copies of 30B parameters. That's gigabytes of VRAM that could be used to store more KV cache entries, process larger batch sizes, and ultimately drive higher throughput.

This is a problem familiar to those in the LLM training world, where sophisticated offloading strategies like FSDP and DeepSpeed ZeRo have been developed to better utilise limited GPU VRAM.

Inspired by this, we introduce Zero Redundency Data Parallelism (ZeroDP), a method to reclaim that VRAM by offloading model weights and pulling them Just-In-Time (JIT) over NVLink. By treating one model instance as a "Source" and others as "Sinks," we can significantly expand the effective memory available for inference without sacrificing latency.

All the code for this work is available at github.com/jamesdborin/zerodp.

Building Intuition: The Arithmetic of Offloading

To understand why this is possible, we need to look at the characteristics of modern LLM workloads and hardware.

- Decoding is Dominant: In many production workloads, the decoding phase (generating tokens one by one) runs for far longer than the prefill phase. Even with long prompts, the serialized nature of decoding means it occupies the majority of GPU time.

- MoE Arithmetic Intensity: Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) models like Qwen-30B-A3B or DeepSeek-V3 have a large number of experts () but use only a small fraction () per token.

- The KV Cache Bottleneck: To make the decoding phase compute-bound (fully utilizing the GPU's tensor cores), you need massive batch sizes—often in the range of thousands of tokens. However, you rarely have the VRAM to support that. On a single H100 running Qwen-30B, you might optimize your way to ~40GB of KV cache. With small requests of just 1024 input / 128 output tokens, that only gets you a batch size of ~350. We are memory capacity bound, not compute bound.

If we can free up VRAM from weights, we can increase batch size. Here is some napkin math for how much we can improve with an FSDP-inspired offloading system for inference:

Consider two H100s connected via NVLink, which offers ~400 GB/s of realizable unidirectional bandwidth.

- If a forward pass takes 50ms, we can transfer of data during that computation.

- That's enough space for roughly 200,000 additional tokens of KV cache for a 16bit cache for Qwen3-30B-A3B.

- If your baseline available KV cache was 40GB, this is a 50% increase in capacity.

If we can mask that transfer latency, that capacity increase is free.

Architecture: Expert Sources vs. Expert Sinks

We deviate from standard Data Parallelism by introducing asymmetry.

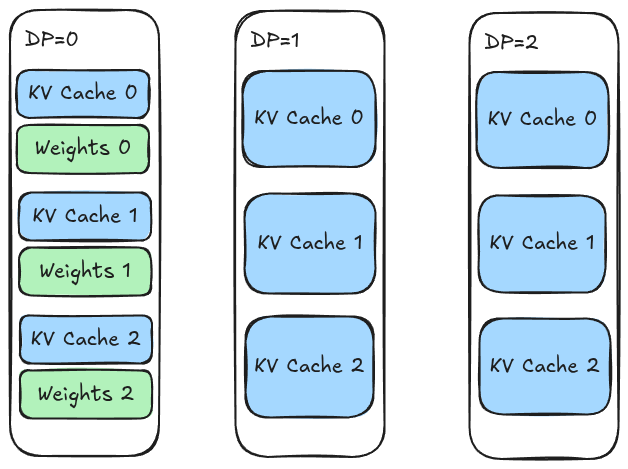

- Source Model: This set of GPUs holds the standard, full copy of the model weights. It operates like a typical inference worker.

- Sink Model: This set of GPUs holds a stripped-down version of the model. We delete the bulk of the parameters—specifically the MoE experts—keeping only the skeleton (attention layers, routers, etc.).

By deleting the experts, the Sink GPU reclaims gigabytes of VRAM, which it reallocates to the KV cache.

Figure 1: Comparison between a Source GPU (full weights) and a Sink GPU (sparse weights).

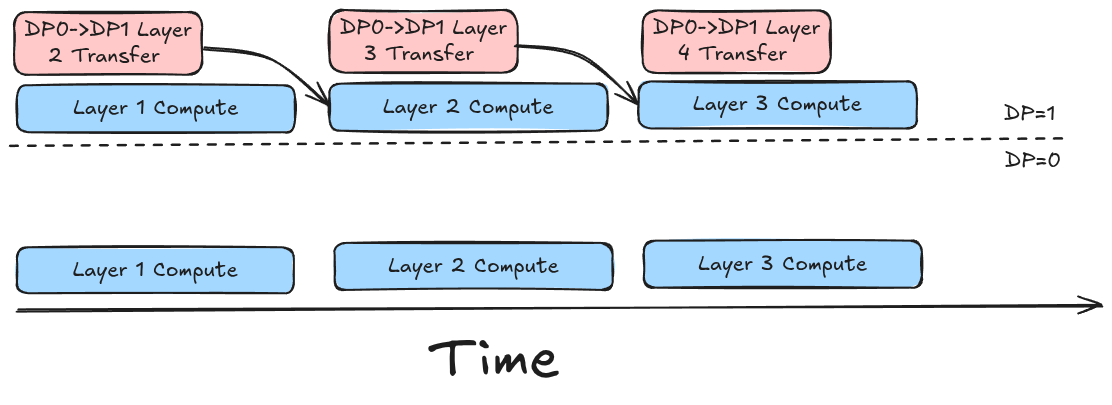

The workflow becomes a balancing act between running available weights on the Sink and pulling weights from the Source:

- Both Source and Sink execute forward passes on different batches of data.

- The Sink reaches a layer where it needs experts it doesn't have.

- It pulls those specific weights from the Source GPU's memory over NVLink.

- It performs the computation.

- It discards the weights to free up the buffer for the next layer.

Technical Implementation

Implementing this efficiently requires solving three problems: bandwidth, overlap, and asynchronous communication.

1. The Interconnect

This technique is uniquely enabled by NVLink. PCIe Gen4/5 (capping at ~64 GB/s) is simply too slow; the amount of data we could transfer in a forward pass just isn't very high. The juice wouldn't be worth the squeeze. With NVLink's 400-900 GB/s, we have enough bandwidth to move heavy expert tensors faster than the GPU can crunch the math on the previous layer.

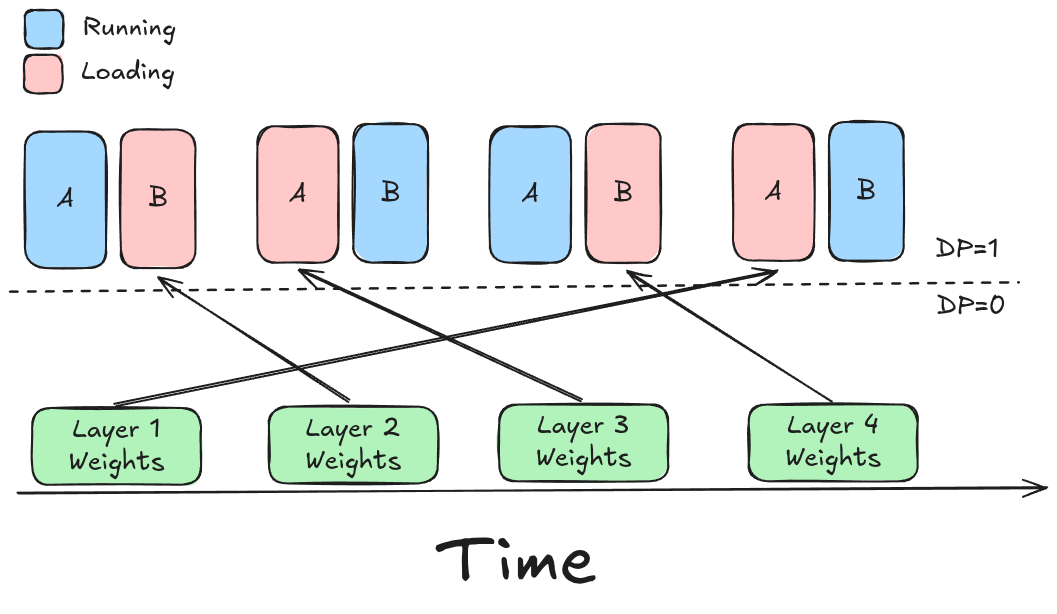

2. Overlapping Compute and Comms (Ping-Pong Buffers)

To ensure zero performance penalty on the Sink model, the weight transfer must be perfectly hidden. We cannot wait for the network to fetch weights when we need them.

Figure 2: Ideal timeline showing weight transfers for Layer i+1 completely hidden behind the computation of Layer i.

Figure 2: Ideal timeline showing weight transfers for Layer i+1 completely hidden behind the computation of Layer i.

We implement a Ping-Pong Buffer strategy on the Sink GPU:

- Buffer A: Holds weights for Layer . Currently being reading by the Compute stream.

- Buffer B: Being filled with weights for Layer by the Communications stream.

The compute stream for Layer cannot start until Buffer B is full and Layer is finished. If tuned correctly, the transfer into Buffer B finishes before Layer computes, effectively making the network operations invisible to the overall runtime.

Figure 3: Ping-Pong buffer orchestration. While Buffer 1 computes Layer 1, Buffer 2 fills with Layer 2.

Figure 3: Ping-Pong buffer orchestration. While Buffer 1 computes Layer 1, Buffer 2 fills with Layer 2.

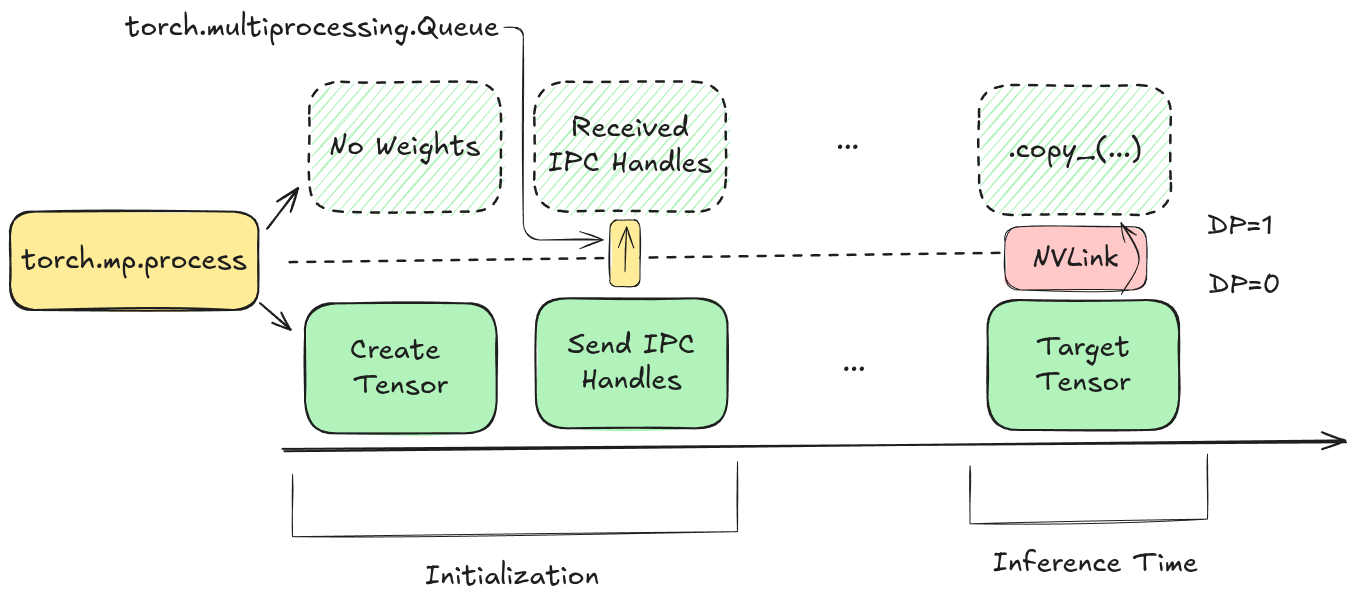

3. Asynchronous Communications (CUDA IPC)

This is the most critical software challenge. Standard distributed training offloading (like ZeRO-3 or FSDP) relies on collective primitives (like ncclAllGather). These collectives are synchronous: all ranks must enter the communication kernel simultaneously.

In inference, our Source and Sink instances are processing completely different requests. They are inherently asynchronous. We cannot force the Source to "stop and send" when the Sink is ready, as that would kill the Source's throughput.

Instead, we use CUDA IPC (Inter-Process Communication).

- The Source process exports a handle to its GPU memory.

- The Sink process imports this handle, mapping the Source's memory into its own virtual address space.

- The Sink initiates a one-sided

torch.copy_(orcudaMemcpyAsync). The Sink "pulls" the data without the active participation of the Source's process.

This decouples the control flow. The Source crunches away on its batch, oblivious to the fact that the Sink is reading from its HBM.

This means the Source runs at the exact same throughput that your usual deployment does, while your sink is able to operate at a higher batch size, with completely overlapped comms. A rare free lunch!

Figure 4: Using CUDA IPC handles to enable one-sided memory pulls from the Source GPU without synchronization.

Figure 4: Using CUDA IPC handles to enable one-sided memory pulls from the Source GPU without synchronization.

Results & Benchmarks

We validated this approach on an H100 setup with Qwen-30B-A3B.

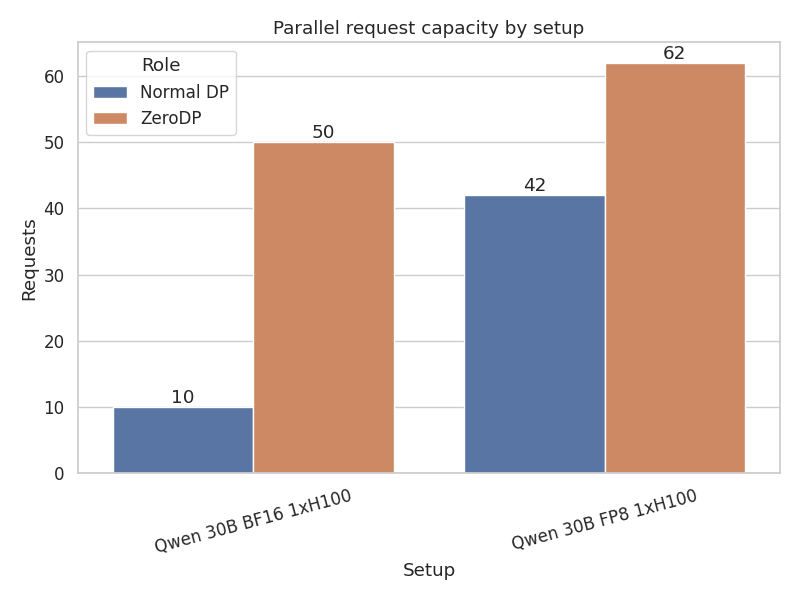

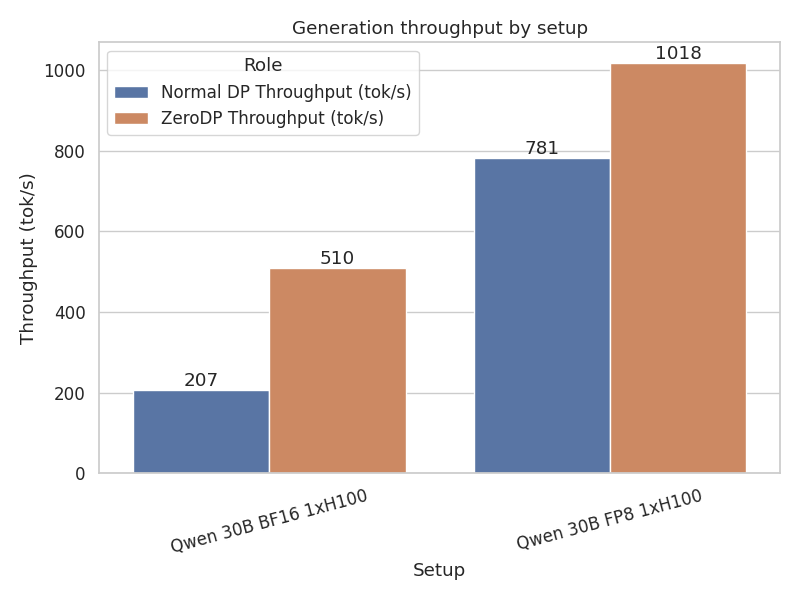

Case A: Qwen 30B-A3B In BF16 1xH100 In BF16, the model weights are large, and the KV cache pressure is high. This is the "most favorable" scenario because the compute intensity is high enough to hide large transfers, and the memory savings are significant.

- Throughput: The Sink instance achieved a throughput of 510 tok/s, vs the Source instance of 207 tok/s, a 2.5x improvement!. Compared to a standard DP=2 setup ZeroDP is 1.7x faster.

Case B: Qwen 30B-A3B In FP8 on 1xH100 In FP8, the weights are smaller, and the baseline batch sizes are already larger. The relative gain from freeing up memory is slightly lower, and bandwidth requirements drop by half, decreasing the capacity to overlap compute with communication.

- Throughput: The Sink instance ran at 1.30x the speed of the Source, 1018 vs 781 tok/s. Compared to DP=2, ZeroDP has a 1.15x higher peak throughput.

Figure 5: ZeroDP delivers higher peak generation throughput by freeing up GPU VRAM for the KV Cache - allowing more requests to run in parallel than standard Data Parallelism

Figure 5: ZeroDP delivers higher peak generation throughput by freeing up GPU VRAM for the KV Cache - allowing more requests to run in parallel than standard Data Parallelism

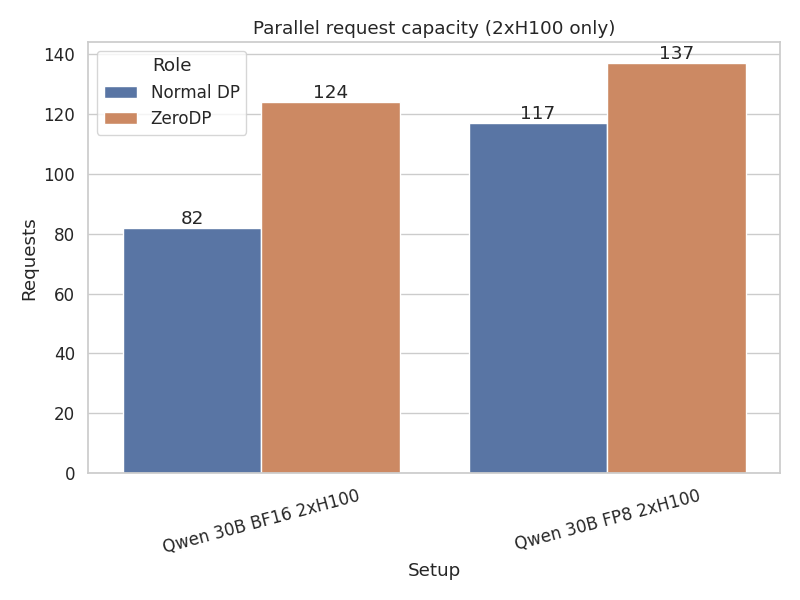

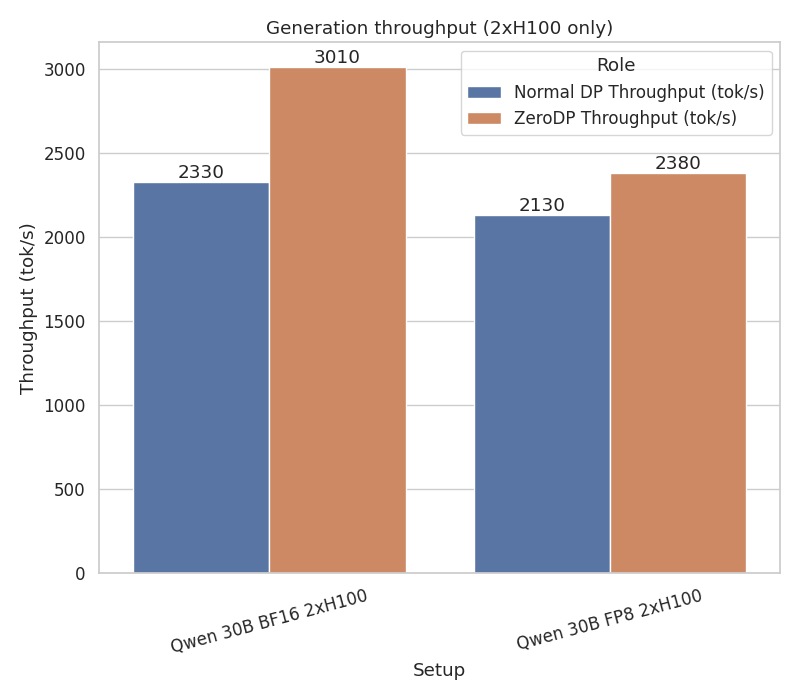

Case C: Qwen 30B-A3B In BF16 on 2xH100 With a 2-GPU setup, running the models in Tensor parallel we still see the benefit. In this setup each TP or EP rank has its own queue that connects it with the same TP/EP rank in the other DP rank. Other than that all other logic remains the same. Higher TP degrees mean there is more space available for the KV Cache, so the roofline percentage changes in throughput and occupancy goes down. However it also means that we can use multiple NVLink connections and are transporting smaller tensors across NVLink so any movement overhead is reduced.

- Throughput: The Sink instance achieved 3010 tok/s compared to the Source's 2330 tok/s, a 1.29x improvement. Compared to standard DP=2,TP=2 setup, ZeroDP achieves 1.15x higher aggregate throughput.

Case D: Qwen 30B-A3B In FP8 on 2xH100 In FP8 with 2xH100, the memory savings are still meaningful but the percentage gains are more modest as the baseline is already quite efficient.

- Throughput: The Sink instance ran at 2380 tok/s vs the Source at 2130 tok/s, a 1.12x improvement. Compared to standard DP=2,TP=2, ZeroDP shows 1.06x higher peak throughput.

Figure 6: With 2xH100, ZeroDP continues to demonstrate throughput improvements by maximizing KV cache capacity through weight offloading

Figure 6: With 2xH100, ZeroDP continues to demonstrate throughput improvements by maximizing KV cache capacity through weight offloading

Challenges & Future Work

There is no free lunch (just cheaper lunch).

- NVLink Saturation: As you add more Sink models to a single Source, the Source's egress bandwidth splits. A single Source cannot feed an infinite number of Sinks.

- Topology Matters: This requires direct NVLink connectivity. Multi-node setups or PCIe backplanes will be harder to make work.

- Diminishing Returns: At extremely high degrees of parallelism, the weight matrices become a smaller fraction of total memory compared to the massive KV caches, reducing the relative impact of this optimization.